The majority of Greek and Hindu philosophy was written during the late BC period during a time of extreme philosophical productivity. This was not the only period in which philosophical advancements were made, but it was probably the most productive in documented history. However, according to the traditionalist Coomaraswamy, Greek and Hindu metaphysics are to be conflated with each other in what is essentially the only possible metaphysics. What I am arguing is that there are structural dissimilarities between Greek and Hindu philosophy- the two being inverses of each other.

Coomaraswamy and Radhakrishnan

There are really two types of Indians, there are Coomaraswamy Indians and Radhakrishnan Indians. Radhakrishnan Indians attempt to distinguish Greek and Hindu metaphysics as much as possible and see the Indian metaphysics as resembling the closest that of modern idealism, while the Coomaraswamy Indians see Indian philosophy as essentially Greek- or do they see Greek philosophy as essentially Indian. Coomaraswamy was really building off of the work of two catholic philosophers: Rene Guenon and Julius Evola, who classify the work of the Indians as esoteric- to be grouped in the same category as Islam, Judaism, Catholicism, Buddhism, and Taoism. Coomaraswamy really must not have followed the same mold, and although his analysis of Hindu art should be labeled traditionalist, he must really be an ordinary Indologist equipped with the ordinary language movement. Thus Coomaraswamy is probably more popular with the Western audience, but in reality, Radhakrishnan is probably correct.

Difference Between Greek and Hindu Philosophy

Greek philosophy and Indian philosophy are really structurally distinctive entities- the two being inverses of each other. Indian philosophy is really around 70% esoteric and 30% philosophy, while Greek philosophy is 70% philosophy and 30% not esotericism, but spirituality, which is uses a looser epistemic framework in which to make transcendent claims. The reason that Indian philosophy should be considered esoteric is that the Indian philosophy is documented in a divine language with many indications pointing to the fact that it is describing a true facet of reality. This seems to be lacking in its Greek counterpart. But if you want to drop the esoteric-spiritual distinction, the fact is that Indian philosophy is mostly transcendent, while Greek philosophy is mostly transcendental. I didn’t say one was superior to the other, but one has to take his pick where his interests lie. Does he prefer transcendence or does he prefer the transcendental. Me personally, I believe I have philosophical talent and in fact the vast majority of what I was doing in my late teens and early twenties was philosophical metaphysics- the reconstruction of modern idealism- but my interests tend to lie in transcendence. So I didn’t say one was superior to the other, but the differ in this regard.

Defense of Greeks more transcendental nature

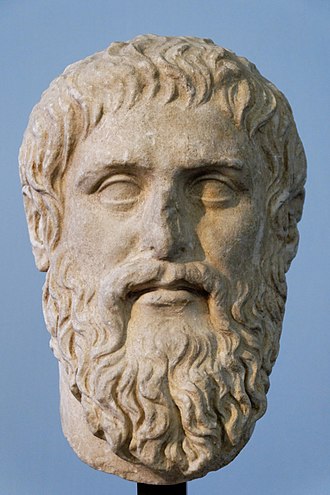

The presocratics are transcendental. The Ionian philosophers with all is fire and all is water and so forth- you can give arguments for that. Some of the Ionian philosophers posit non-elaborate cosmologies such as that the earth is flat and is surrounded by balls of fire- but this is a small amount of transcendence. The rest of the presocratics are transcendental. The sophists are rational in nature, the Pythagoreans with all is number- you can give arguments for that and the atomists are rational. Clearly, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle are more transcendental in nature. The stoics posit the metaphysical entities of fatalism and realistic pantheism but that is only two metaphysical entities, and you can give arguments for that. Further, it is well documented among professional philosophers that although stoicism is metaphysical in nature, the emphasis of stoicism and the vast majority of its thought is on ethics. Skepticism is clearly rational. Finally ancient Greek philosophy gets into the purely ethical theories of epicureanism and eclecticism. These are very transcendental in nature.

On the other hand, Indian philosophy is mostly transcendent in nature. The Naya creates the epistemic framework in which to make transcendent claims. The Vaisesika and Jainism posit a host of atoms that transcend reason. The Samkhya gets into the transcendent entities of sattva, rajas, and tamas. The Yoga deals mostly with the paranormal. Also, the Mimamsa deals mostly with the rituals of the Vedas. The Vedanta posits the transcendent entities of maya, jiva, karma, moksa, and future life. Finally, Buddhism and Jainism posit elaborate cosmologies with many transcendent entities.

Further structural differences between Greek and Hindu philosophy

many ordinary language philosophers would believe that Radhakrishnan and the people of the early nineteen hundreds were at a low point- they had inadequate knowledge of Greek philosophy and were simply reiterating what came in the past. From the perspective of metaphysical structuralism, Radhakrishnan had adequate knowledge of Greek philosophy and it was Coomaraswamy who made the error.

There are further structural differences between Greek and Hindu philosophy. Even at points were Indian philosophy and Greek philosophy seem to be identical, there are structural differences between the two. The atoms of the Greeks are quantitative, while the atoms of the Indians are qualitative and transcendent. Both the Greeks and the Indians posit categories, but the categories of the Indians are different from the categories of the Greeks. It is true that Plato posits a transcendent God and an eternal world but Plato’s god is fully transcendent; the idea of objective idealism, in which there is a transcendent god that contains the world in his consciousness is an Eastern conception that was invented by the Indians. And this has consequences of a peaceful and female centric society. I have Neoplatonism as an extension of Platonism. That is, Neoplatonism is essentially an epistemic idealism and the merging with God takes place fully within the person’s brain. And this merging with God has more to do with a feeling of closeness than with an increasing of intellectual capabilities. Finally, maya which seems on paper to be saying something similar to skepticism really has nothing to do with skepticism. Maya is a metaphysical claim and skepticism is an epistemological claim. If you can’t see the difference between maya and skepticism, look at the difference between cricket which is maya based and Greco-Roman wrestling which is skepticism based. Cricket and wrestling are really completely different sports from each other, and you can see through these sports the difference between these two entities.